|

Eager Space | Videos | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

We all know that orbital rockets are hard to build.

It takes a lot of money and technical ability to build rockets that can actually make it to orbit without blowing up.

But once you have that orbital rocket, you'll be able to fly payloads to space and make a lot of money, right?

You will be able to fly payloads to space. Whether anybody will *pay* you to launch those payloads or whether you will make money on those launches is an open question.

That depends upon what kind of payloads customers are wanting to launch and who your competition is.

It's about the launch market.

We're going to start by looking at a market that I think is easier to understand than rockets - the market for tortilla chips. As is usually the case, I'm going to be simplifying a lot of the underlying concepts.

In most cases, there isn't just one market but a bunch of different market segments because consumers want different things.

For example, there is one set of consumers who want plain tortilla chips, and we can call them a separate market segment, or a market all by themselves.

There's a segment of plain chip buyers composed of consumers who are very price conscious. That's another segment.

And then we have endless flavors of chips. There's a segment of consumers who are hooked on doritos nacho cheese flavor, and even on the Taco flavor.

If we want to start our own chip company, it's going to be difficult.

The plain and plain/cheap segments have lots of other companies already competing with each other.

These two doritos flavors have been in production for more than 50 years, and the chance of coming up with a product that can steal away those customers is minimal.

In general, the goal with a new business is not to go where the competition is strong but go where the competition is weak and/or where they are unable to easily go.

So maybe you could come up with something like organic corn chips, or tortilla chips made out of something other then corn. These are better strategies because they are harder for a big company like Frito Lay to follow.

When looking at a company and their chances of success, we need to understand what the markets are and what other players there are in the markets. Is the market very competitive, like the chip market? Or is there a lack of competition in a market that leads to opportunities for new companies.

Business success requires both a good product and a market - or market segment -that gives opportunities for success.

My first question about companies isn't "what are they doing?", it's "what is their target market?", because if there is no market opportunity, they cannot succeed.

Let's take those basic principles of markets and apply them to the rocket world.

And let's look at the market back in 2005, at a time when a certain space company was very young.

We'll start with the commercial satellite market, which was mostly dominated by communication satellites that were launched to geosynchronous transfer orbit, or GTO. This is the most competitive of the launch markets - all you need to do is show up with a rocket that can put these satellites in the desired orbit to join the market.

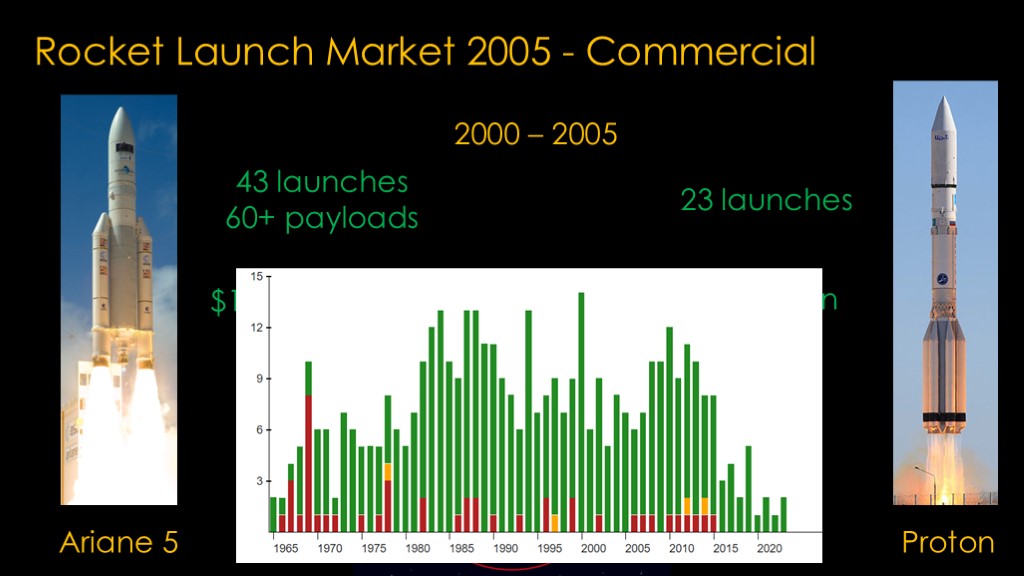

In 2005, this market was dominated by two launchers.

The European Ariane is the market leader. Ariane 5 is a little weird in that it typically flies GTO missions with two payloads - typically one on the larger side and one on the smaller side - so it gets more than one payload per launch. This dual launch makes the launch cost of $150-$200 million a bit more acceptable. Ariane is launched by ArianeSpace, which is a company owned by 17 European suppliers of Ariane components across 9 countries so it is not the most agile of companies.

From 2000-2005, Ariane flow 43 missions and over 60 payloads.

The second major launcher is the Russian Proton. The Proton is quite a bit cheaper at roughly $65 million per launch, but it unfortunately has a problem. If we look at its launch history, it fails a lot - roughly 10% of the time. In 2000-2005, Proton launched 23 commercial satellites.

There's an obvious question to ask here - why are people willing to risk their business on a launcher that has such poor reliability?

The answer is simple. There is more demand to launch satellites than there is Ariane launch capacity, so from a business standpoint it's better to take the risk of losing the satellite - and the revenue it will generate the next few years - versus the certainty of losing the revenue if you wait to launch on Ariane.

That's one supplier who is great at reliability and service but is expensive and isn't terribly agile, and a second supplier who's a lot cheaper but has reliability problems. And there is a backlog of payloads waiting to be launched.

It appears there is a significant opportunity here if a reliable low-cost launcher were to show up.

The second market is launching general payloads for the air force or launching NASA's science payloads.

Each of these programs have their own requirements, and the requirements to bid on these launches depend on the payload - important payloads require a proven track record, while less important payloads require less of a track record. NASA in particular will fly low-priority payloads on unproven rockets as part of their charter to help commercial launch companies wherever possible.

As the main US commercial launch company in 2005, United Launch Alliance launches the majority of these payloads. Currently there is little competitive pressure on them to launch these missions at low prices.

Another market opportunity for any launcher that can meet the qualification requirements.

The department of defense / air force has a program to launch their important satellites known as the evolved expendable launch vehicle program, or EELV. The program is now known as NSSL, or National security space launch.

Many of these launches are to orbits above low earth orbit and therefore require high performance launch vehicles.

The air force launches many military satellites under this program, and the launchers they used were the Atlas V or the Delta IV.

They are both owned by the United Launch Alliance, a company half-owned by Lockheed Martin and half owned by Boeing that was created in a shotgun wedding brokered by the government when Boeing was found to have committed industrial espionage against Lockheed martin and was therefore barred from competing for government contracts.

For that story, see my video "spies, allies, and enterprise - the strange story of ULA".

The upshot of this arrangement is that ULA has a monopoly on launching payloads and not only are they charging high prices per launch, they are receiving "launch capability payments" from the government for being capable of launching even if they don't have payloads to launch. This is a very lucrative business to be in.

A new launch vehicle could likely take away some of this business, as the government would prefer not to rely on a single company.

There are significant performance and reliability requirements to be able to fly these missions and that sets a high bar for any new company, but a company that can meet those requirements can charge a premium for these launches and still be cheaper than the Atlas V and - especially - the Delta IV Heavy. These launches are rewarded in chunks so it will be very hard to unseat a company launching under this program.

Definitely a market opportunity.

There is one more market, and it's a brand new one.

In 2005, NASA was in the process of spending about $150 billion to complete the international space station.

When completed in 2010-2011, the shuttle would be retired. The shuttle was the only US vehicle that could carry cargo and crew to the space station. Without a new capability, the US would be forced to rely on the Russian progress vehicle to carry cargo and the Russian Soyuz to carry astronauts.

Not a good look for NASA.

In 2005 NASA was spinning up the Constellation program, and the plan was that the Ares I rocket with the Orion capsule on top would take over for the shuttle in carrying crew to ISS.

It wasn't a very good plan - Ares I was going to be very costly to develop and Orion was overengineered for an ISS capsule. The program was just getting underway in 2005, but it was looking to be very costly on a per flight basis, with $1 billion or more per flight showing up in later estimates. It was moving slowly as well.

NASA needed something a *lot* cheaper to get cargo the ISS and it would be really useful if it were ready when shuttle retired.

NASA spun up two programs - a development program named commercial orbital transportation services and an operational program named commercial resupply services.

This was a huge opportunity. An operational contract would likely mean 2 launches per year for many years and they would likely be lucrative. And the program required a capsule to dock with the ISS, so it wasn't purely about launch, and that made it harder for existing launch companies to compete.

There would also likely be a follow-on program to launch crew to ISS to remove the dependency on the Russians, and that could be another lucrative long term project.

To summarize, in 2005 there were significant opportunities in 4 different launch markets. One was a new opportunity, and the other 3 had companies that were not particularly agile.

This was a perfect time to start a rocket company with a medium lift rocket, if only that rocket company could actually build such a rocket.

Obviously SpaceX did get there with the Falcon 9.

In addition to the market opportunities, SpaceX had some other things going for them.

Musk had seed money from his sale of Paypal, and that reduced the amount of outside investment they needed.

Musk had connections to silicon valley investors that could be tapped for development money.

SpaceX had Gwynne Shotwell who had a deep understand of the launch market, and her ability to sell launches on the unproven Falcon 9 to companies that would have launched on Ariane or Proton was critical.

SpaceX was fast moving and very cost sensitive, especially when compared to the existing launch companies.

SpaceX won the COTs contract for ISS cargo, which gave them development money they could definitely use.

And even with very favorable market conditions and development money from NASA, it was a close thing - SpaceX could easily have gone out of business during this period.

SpaceX is a remarkable company but their success relied on market opportunities that they could exploit.

How has the launch market changed since 2005?

Ariane 5 launched 9 times in 2020-2023. Note that this was during the pandemic years.

Proton has pretty much disappeared as a commercial launcher.

Ariane 5 has flown its last flight, and we are now waiting for the first flight of Ariane 6, current scheduled for sometime in 2024.

Because of the delays in Ariane 6 development, there is a year or two of governmental payloads to launch before Ariane 6 can get back to launching commercial payloads.

Proton was obviously replaced by Falcon 9, and from 2020-2023, Falcon 9 has made 19 launches to geosynchronous transfer orbit, the same that Ariane 5 did.

The launch market to GTO is much cooler than in 2005, with many companies trying to understand how starlink might affect their business.

Even with Ariane currently on a break, Falcon 9 could launch more if necessary and it is the price leader in this market, so the market opportunity here is gone.

For the Space Force and NASA payloads, SpaceX is winning pretty much all of the independently bid contracts, so much so that ULA has declined to bid on some of them.

There is still a market opportunity for new launchers to win the launch contract for the NASA payloads that require less reliability.

The current version of National security space launch has contract awards split between United Launch Alliance, who gets 60% of the launches and SpaceX who gets 40% of the launches.

United launch alliance flies both the Atlas V and Delta IV Heavy for these missions, while SpaceX flies both the Falcon 9 and the Falcon Heavy.

Like Ariane, ULA is in the midst of changing rockets, with ULA hoping to fly their Vulcan rocket in 2024.

This has been problematic for ULA; Vulcan needs to fly 3 times before it can fly the NSSL payloads, and it is possible that some of the payloads will be shifted to SpaceX or perhaps launched on one of the few remaining Atlas V rockets if Vulcan is further delayed.

This will get interesting during the next phase of NSSL, as ULA and SpaceX are very likely to win the contracts they have won in the past, but a new "lane" will be added for competitive launches.

That will add new opportunities for companies to bid on, assuming they are cheap enough to beat SpaceX.

For resupply cargo flights to the ISS, SpaceX shares the contract with Northrop Grumman.

For crew flights to the ISS, SpaceX shares the contract with Boeing, though SpaceX is on their 7th operational flight and Boeing has yet to fly a crewed mission.

It is unlikely that any of these providers will be replaced for the remaining lifetime of ISS.

Unlike 2005, in 2023 there are few significant opportunities and you need to compete with SpaceX in most markets.

Is there a way to compete with Falcon 9 with a small rocket.

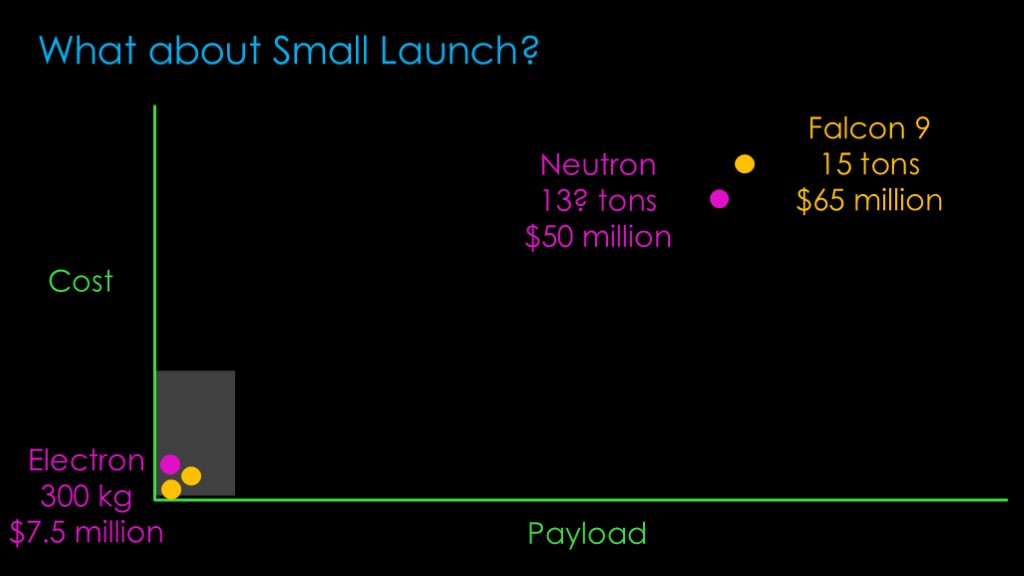

Falcon 9 is a medium lift rocket that can lift about 15 tons into low earth orbit for $65 million.

There's a region at the left side of the graph that is classified as "small lift launch vehicles. Is this a market opportunity?

Rocket Lab's electron lives way down here at the left edge. It can launch 300 kg payloads for only $7.6 million. It has 36 successful launches. Their payload is small but they have commercial customers who are designing to that payload size.

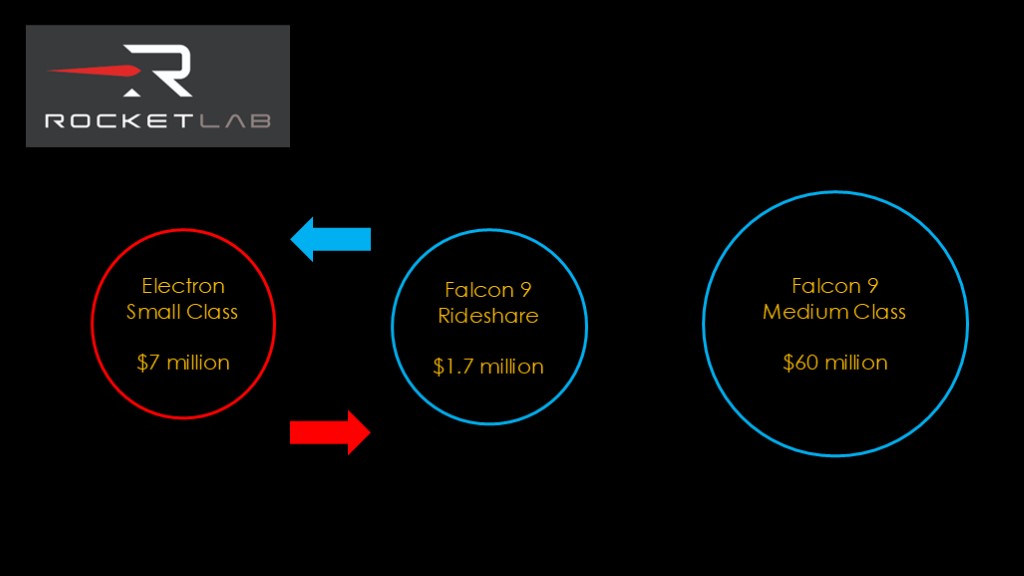

SpaceX also competes here, with their rideshare flights that are cheaper than Electron if you are okay with their scheduling and their target orbit. SpaceX also supports larger payloads on the rideshare but does not publish their launch prices.

So the answer is that Rocket Lab is already there and competitive and SpaceX is vacuuming up all the companies who care most about price, so there is very little market left for companies that want to compete in the small launch market.

This is apparent to Rocket Lab, which is why they are working on the Falcon 9 - class Neutron rocket.

Atlas V - $109 million to $200 million

Delta IV Heavy - $350 million to $400 million

Vulcan - $110 million?

New Glenn - Who knows? $90 million to $250 million

Ariane 6 - $77 - $126 million

Falcon Heavy - $97 million

Neutron - $50 million

Starship - $15 million to $200 million

It gets worse for new companies.

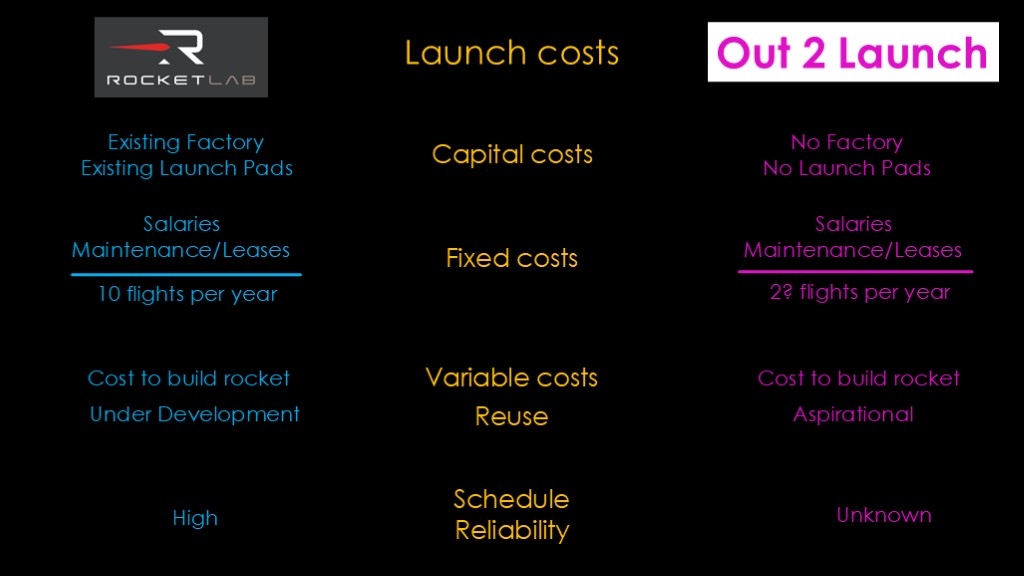

Let's compare Rocket Lab to a hypothetical new launch company, looking at their cost structures.

Rocket lab has an existing factory for building rockets and multiple launch pads. Our new company has neither of those, so they will need to pay to build them.

There are fixed costs, which are primarily employee salaries plus maintenance costs and the cost of leased equipment and buildings.

Those fixed costs are spread across the number of launches the company manages per year. Rocket lab is on track to launch at least 10 times in 2023, so each launch needs to pay 10% of their fixed costs. Our new company would be lucky to fly twice a year, so at best each launch needs to pay 50% of their fixed costs.

This is a *huge* problem for new companies. You need a high flight rate to get enough business to spread you fixed costs out enough to get a competitive price, but you can't get a high flight rate without a competitive price.

There are also variable costs. Rocket Lab has flown 39 electrons and they are now building a production version of the rocket using an optimized factory process. Our new competitor is building prototype rockets and making changes along the way, and that is inherently a more expensive approach.

Rocket lab is currently developing reuse of their first stage, and hopes to fly a previously-flown stage in the near future. That has the potential to both reduce their per-launch variable costs and also allow them to increase their flight rate. Our new entrant wants reuse - and perhaps is in a better position to design in reuse rather than add it on as Electron has - but when entering the market it's just aspirational.

All of these factors give the established company a significant launch cost advantage over the new entrant.

And there's the additional factor of schedule and reliability. You can call up Rocket Lab to schedule a launch and they will give you a firm launch date, and with 19 successful flights in a row, your launch is likely to be successful. Our new competitor can provide neither a firm date nor a high chance of success.

And that's why starting a launch company is a bad decision...

If you enjoyed this video, build and launch a model rocket.

Pro tip: Never go to launch rockets with only one rocket as you may return home with zero rockets.

I suggest a rocket box...

There is a strategy in business known as "fast follower", where you wait for a company come up with a great idea and develop it and then you swoop in and utilize your advantages to out-compete them in this new area.

I think there may be some examples of that happening in the software industry, but I'm quite sure that it's not going to happen in the launch industry. The majority of the market opportunities that SpaceX took advantage of are gone and to compete in those segments you will need to compete with SpaceX.

But there might be a way...

Amazon's project Kuiper is under development, and it's a competitor to SpaceX's starlink space-based internet project.

Because of that, Amazon has no interest in sending SpaceX money to launch their satellites, so they've created a new market segment which I call "anybody but SpaceX"

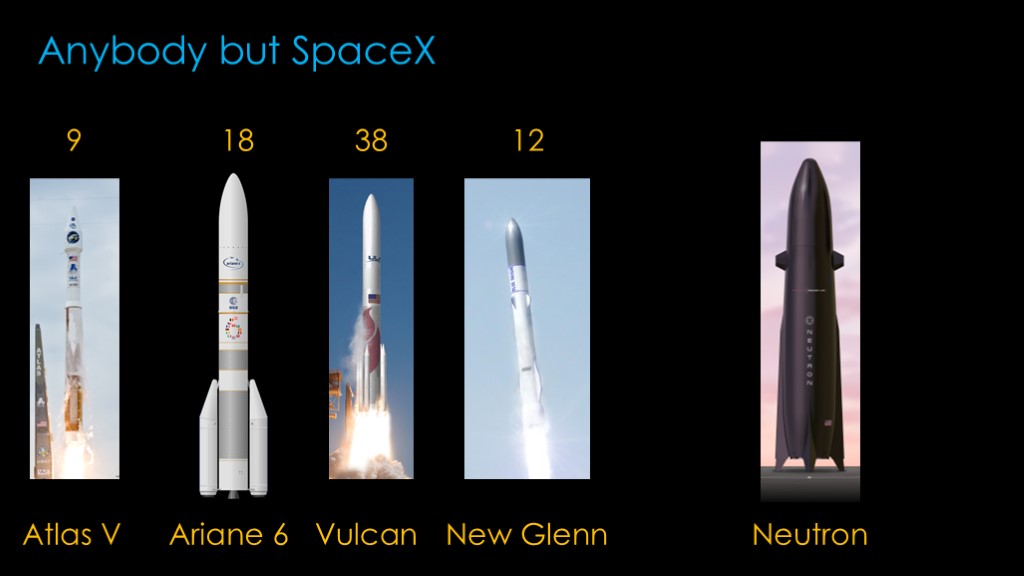

Project Kuiper will require a very large number of launches to finish their constellation of 3236 satellites. Amazon has reportedly bought the last 9 Atlas V rockets for launch. They have also bought launches on 3 new rockets, with 18 launches on Ariane 6, 38 launches on ULA's Vulcan, and 12 launches on Blue Origin's New Glenn.

I suspect that there may be undisclosed purchases to fly on Rocket Lab's Neutron rocket, also currently under development.

If a new entrant could create a rocket that would be able to lift Amazon's satellites economically, I'm sure Amazon would buy launches from them, but all of these are big medium-class or larger rockets and that's a hard rocket to develop for new companies.

SpaceX and Rocket Lab are both successful launch companies.

SpaceX is currently dominating the worldwide launch business, but they understand that they can only keep high margins there as long as there isn't significant competition. They are diversifying into satellite internet with Starlink and leveraging their ability to launch cheaply on Falcon 9 - and someday, on starship. And that puts them into the "satellite bus" market as well...

Rocket Lab is perhaps more interesting. They have diversified into hypersonic test, a market where electron is a good fit for the market.

With the money they got when they went public, they diversified into space systems - reaction wheels, star trackers, radios, software, solar panels. That market is one that had not yet been disrupted and they currently make more money off of space systems than launch.

They are also building Neutron, my bet for the first Falcon 9 competitor that will fly. That will allow them to compete for some department of defense launches, and it will also set them up very nicely in the "anybody but spacex" market segment for customers who compete with SpaceX and therefore don't want to give them launch money.

The second company to start up around that time was Rocket Lab, though it took a few years for them to get funding to work on their Electron Rocket and it didn't fly until 2017.

(show electron )

Rocket Lab's target is small launch, with a payload of approximately 300 kg. It's much smaller than the payload of SpaceX's Falcon 9, but it's much cheaper. It would seem that Electron has that market sewn up, but SpaceX has recently been flying rideshare missions where it caries numerous payloads in one launch, and a 300 kg payload on a rideshare is only $1.7 million, much lower than the cost of an electron launch.

This is widely viewed as problematic for Electron, but I'm not sure as markets are weird things. Electron provides flexibility in launch timing and orbit selection that the Falcon 9 rideshare cannot.

It might be that the Falcon 9 rideshare pulls business away from Electron. And it might be that some of the new companies flying on Falcon 9 rideshare for testing their satellites choose Electron when they fly their production satellites.

At this point one of you is saying "what about rocket lab?" That's a great question, thanks for asking.

Electron can carry 300 kg into low earth orbit for about $7.5 million. Which is a lot cheaper than a Falcon 9 launch.

Unfortunately, SpaceX has a rideshare program where you can send a 300 kg into a low earth orbit for $1.65 million.

So Electron's real market is customers who want to fly to LEO in a very specific orbit.

And there is a market there - they did 9 launches in 2022 and will likely hit the same in 2023. And they've come up with a new application for electron - using the first stage as a hypersonic test vehicle. They are currently making money on launch but not a lot.

- customer who have small payloads that they want to put into very specific orbits and are willing to pay a premium for that.